270 lives ended in one horrific moment on December 21, 1988 when a terrorist bomb planted by Libya destroyed New York-bound Pan Am Flight 103 over the quaint, rural village of Lockerbie, Scotland, 38 minutes after takeoff from London’s Heathrow airport.

In that moment began a heartbreaking new reality for thousands of victim relatives who experienced the worst act of terrorism against America before 9/11.

SINCE: THE BOMBING OF PAN AM FLIGHT 103 is a documentary feature film that tells the story of a handful of those victims and their families, as well as the strong group of survivors who banded together for a difficult fight for truth and justice.

Artist Suse Lowenstein lost her 21-year-old son Alexander aboard Pan Am Flight 103. She stands among Dark Elegy, a larger-than-life-size sculpture depicting more than 80 women – all related to victims aboard the flight – positioned in the horrific, life-changing moment in which they learned that the plane had crashed.

For Lowenstein, the moment of learning her son was dead came from a phone call from one of his friends.

"It felt like everything I had was just sucked out. It was draining out of me, and I knew instantly, truly, that Alexander was dead," says Lowenstein, upon finding out that Flight 103 had crashed.

Suse Lowenstein in her studio.

Lowenstein conjured Dark Elegy as a means of healing through self-portraiture. Soon after the disaster, she began to sculpt herself in the moment that she knew her son was dead. Later, at a bereavement meeting for victims’ relatives, she was struck with the idea of expanding the project to include as many family members as possible, so she placed an ad in the newsletter inviting them to pose. Only women - mothers, daughters, wives, sisters, grandmothers - accepted the invitation.

Miniature figurines of Dark Elegy in Lowenstein's studio.

The sculpture took 17 years to create and sits in Lowenstein’s yard, which is open to the public. She is planning to put the bulk of the $10 million dollars that her family received from Libya as compensation for the bombing towards casting Dark Elegy in bronze and donating it to a public place where as many people can see it as possible.

Dark Elegy in Lowenstein's Montauk, NY sculpture garden.

"The bodies would fall back to that very moment. Some would scream and howl; some would pull their hair, bang their fists on the ground, call their loved ones name," says Lowenstein, of the intimate sessions with family members who posed for Dark Elegy.

Alexander Lowenstein was an English major at Syracuse University when he was murdered on Flight 103. He was an avid surfer and enjoyed staying out past his curfew when the surf was up.

"He wasn't very good in following orders. And in retrospect, we were very grateful that he did exactly what he wanted to do because his life was cut so short," says Suse Lowenstein, of Alexander.

Suse and Peter Lowenstein at their home in Montauk, New York.

In the days following the bombing, victim families were forced to endure the callousness of a United States government that was completely unprepared for a massive act of terrorism like Pan Am Flight 103. The Lowensteins, like scores of other traumatized families, received their son’s remains at the livestock quarantine section of New York’s JFK Airport, where Alexander’s body was unloaded off a spray-painted truck by a forklift and dropped at their feet.

Coffins containing victims' remains lined up in the Lockerbie town hall, before they were "shipped" home.

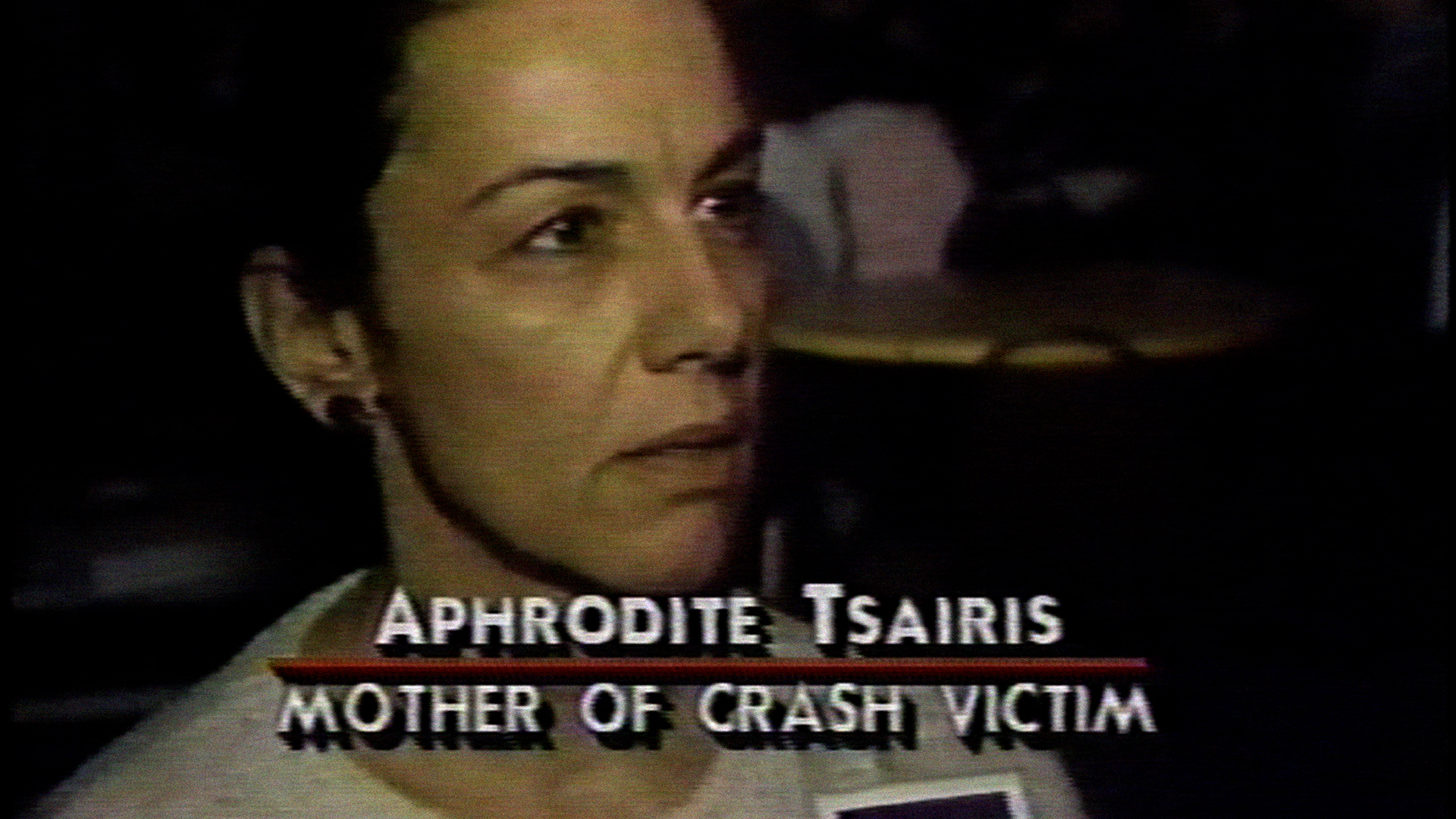

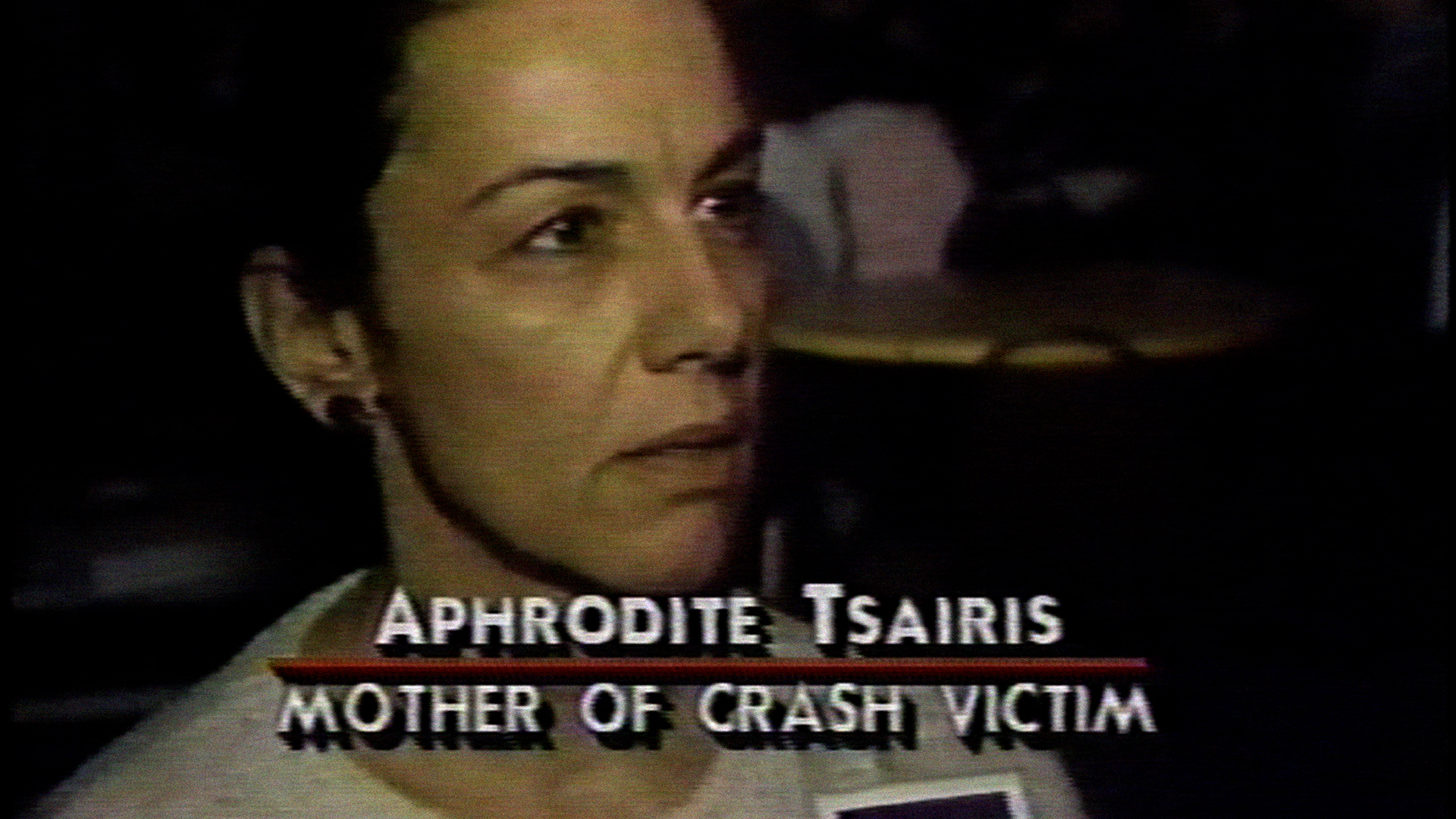

Aphrodite and Peter Tsairis have built their lives around photography since the death of their beloved daughter Alexia, 20, who had pursued photojournalism at Syracuse, and aspired to document strife in conflict zones after graduation.

"We dream about what she would have been like." says Aphrodite, of her daughter. "I'd like to think that she would have been an engager of society and a contributor in whatever way she chose."

The Tsairises founded the Alexia Foundation within a year after the bombing. The nonprofit organization provides financial support to professional and student photographers who shed light on various global crises.

Aphrodite and Peter Tsairis reviewing photographs at home in New Jersey.

The Tsairis family has also endowed The Alexia Tsairis Chair for Documentary Photography at Syracuse Universtiy, and they host an annual competition that provides financial awards to both professional and student photographers.

“We have changed in ways that have made us more informed than we would have normally been if we had lived a typical American life, which is what we were living,” says Aphrodite Tsairis on life since the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103.

Alexia Tsairis produced some of her strongest work during her semester in London before the Lockerbie bombing, including a series on elderly residents of Cotswolds, England, which won her a special award. Aphrodite Tsairis believes Alexia was planning to surprise her parents with news of the of the prize upon her return home to New Jersey.

Aphrodite and Peter Tsairis visited Alexia in London during her semester abroad about a month before the bombing, a trip they are grateful to have made.

Aphrodite Tsairis, a former high school English and French teacher and crossword puzzle editor, devoted much of her time after the bombing to finding answers for the crime. She served as chair of the victims' group during the 1990s.

Aphrodite Tsairis is interviewed by media at a meeting for Pan Am Flight 103 victim families one month after the bombing.

Daniel and Susan Cohen hold a picture of their only child, Theodora "Theo" Cohen, an aspiring actress and theater major at Syracuse University, who was murdered along with several of her classmates aboard Pan Am Flight 103.

The Cohens, who were career writers before devoting most of their time to pursuing justice for the crime, admit that the bombing has left them bitterly angry.

"A lot of really good things came out of the love that I had for Theo, and when she died, that love was in many ways, twisted, and made into something bitter and suffering." says Susan Cohen.

Dan and Susan Cohen at home in Cape May Court House, New Jersey.

Theo Cohen had plans to move to New York City after graduation, living her dream of auditioning for Broadway and devoting herself to the life of a working actor.

"She had a real Bette Davis quality about her." says Susan Cohen of her headstrong daughter.

Both Dan and Susan channeled their rage into becoming powerful entities in the international press. The Cohens continue to speak to journalists for stories about the bombing, all in an effort to keep Theo’s memory alive.

"If someone remembers your name, you're not really dead." says Dan Cohen.

Dan Cohen speaking in media at the Pan Am Flight 103 trial at Zeist, Netherlands (left). Susan Cohen speaking to a reporter from her home in Cape May, New Jersey (right).

For some family members, including Susan Cohen, even the time on a clock can bring a sudden reminder of Flight 103.

Libyan spy Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, convicted of the bombing in 2001, had been diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer and was expected to not live beyond three months. However, he lived for three years following his release, having only served just over eight years of his life sentence, roughly 11 days per victim. It was later revealed that rogue Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi had held hostage a trillion-dollar BP oil deal in exchange for Megrahi’s release.

Susan Cohen reads the newspaper the day after the release of the Lockerbie bomber from the Scottish prison on compassionate grounds, in August 2009 (left). Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, in Scotland, boarding plane home to Libya (top right). Al-Megrahi arrives home in Libya after his release (bottom right).

HOPE DRAINS AWAY

Aprodite Tsairis watches justice unravel right before her eyes as the convicted Pan Am Flight 103 bomber, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, is released from prison in August 2009.

Family members of Pan Am Flight 103 victims, including Suse Lowenstein (top right), protest the September 2009 appearance of Libya's Mummar Gaddafi at the United Nations General Assembly.

Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi would later be murdered by his own people during the Arab Spring movement, in October 2011.

270 people perished in the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, including all 243 passengers on the airliner, the 15-person crew, and 11 people in the town of Lockerbie, who were killed when the plane's wreckage rained upon them.

"The ripple effects of something like that are so enormous, that I can only not even fully understand my own tragedy, leave alone all the others. It's just incomprehensible." says Suse Lowenstein, of the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103.

The names of the 270 victims of Pan Am Flight 103 are listed at this memorial in the town of Lockerbie, Scotland.

THE FILM